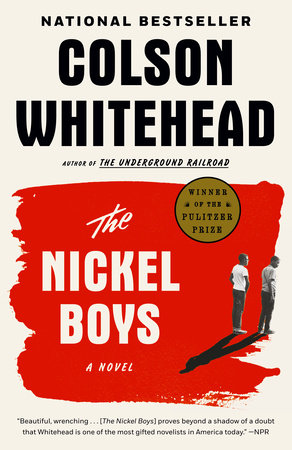

I recently reread Colson Whitehead’s (2019) The Nickel Boys, which seemed more compelling the second time.

This story, which will appear on big screens as a new movie this fall, is based upon an actual Florida reformatory school, which Whitehead reportedly encountered on social media after a local university uncovered unmarked graves on its grounds. From here, he researched and then built a story about 1960s Jim Crow abuse as experienced by two protagonists Elwood Curtis and Jack Turner, which later won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

One reviewer (Rich 2019) claims that this book attests to the American failure to confront its history and to reenact its worst parts. I agree but actually think the book is even more bleak, especially in the way it exposes the limits of literacy and education.

These have been widely believed to be means to liberation, justice, freedom, and independence, which explains why some American slave states prohibited such instruction to African-Americans before and throughout the Civil War. Nonetheless, some, such as Frederick Douglass, would assume great risk to learn to read and write.

These conditions inform the Tallahassee community where Elwood lives. At the same time, he seems oblivious to early warnings, such as the mostly blank encyclopedia set he wins or the circumstances — his commute on the first day of college class — at the time of his arrest.

Such experiences have little effect upon his confidence, which leads him to begin documenting experienced and observed abuses at the school soon after arriving. He later synthesizes these into a written account that he intends to share with government authorities while they’re inspecting the school.

His more cynical friend Turner, who is initially dismissive, later delivers this report when Elwood cannot. Both Elwood and he await an explosive response as do school officials, who relegate him to solitary confinement in case they are asked to produce him.

This anticipated response never materializes, which leads these officials to conclude that they can kill Elwood without risk. At that point, Turner frees his friend and escapes with him only to witness his murder by someone whom they both trusted.

Turner in both a personal tribute and strategic advantage later adopts his late friend’s identity but cannot escape this past. He eventually finds himself staying in the same hotel where Elwood once worked where he anticipates the public testimony he plans to provide, which is where the novel ends.

Turner, and readers, hope that he will join the others and bear witness to and for his friend, and in so doing achieve some justice for him and them. However, Whitehead having seen how the system perpetuates itself can’t help but be skeptical of facts, reason, and argument, and can’t help but wonder if these will betray the Nickel Boys, and all of us, once again.

In this, Whitehead suggests something more than a lack of change. Rather, he pierces hope-filled balloons. How if literacy and education are ineffective do societies achieve accountability and create change?

The Nickel Boys never learned. Neither Whitehead seems to suggest do we.

Leave a Reply