Political violence, which is wrong and isn’t new, seems more widespread after the recent shootings of conservative activist Charlie Kirk on a college campus and liberal legislators Melissa Hortman and her husband and John Hoffman and his wife in their Minnesotan homes as well as the current president while he was campaigning last year.

The current media response however is bewildering, and borderline alarming. Too many seem to not just ignore but even deny the larger contexts. Ezra Klein for example argues that Kirk was “practicing politics in exactly the right way” as if Klein is incapable of acknowledging two truths in tension, or admiring a willingness to debate while condemning a disregard for basic facts and an escalation of political conflicts.

Others have criticized these reactions in the context of Kirk’s efforts and life. Still others have criticized that this tragedy has been politicized by the president and also acknowledged that the most “lethal and persistent threat” in this country comes from white supremacists although some wonder if that is changing, or could change.

I too admire Kirk’s willingness to engage college students on their campuses. I also know that he made mine less effective, and that he was part of a larger problem.

I defined academic appropriateness more narrowly than some colleagues, and limited classroom comments to ones I could connect to my disciplinary domains. I expected, or at least hoped, that the university would defend me from attacks on anything I said about rhetoric, linguistics, or US American literature.

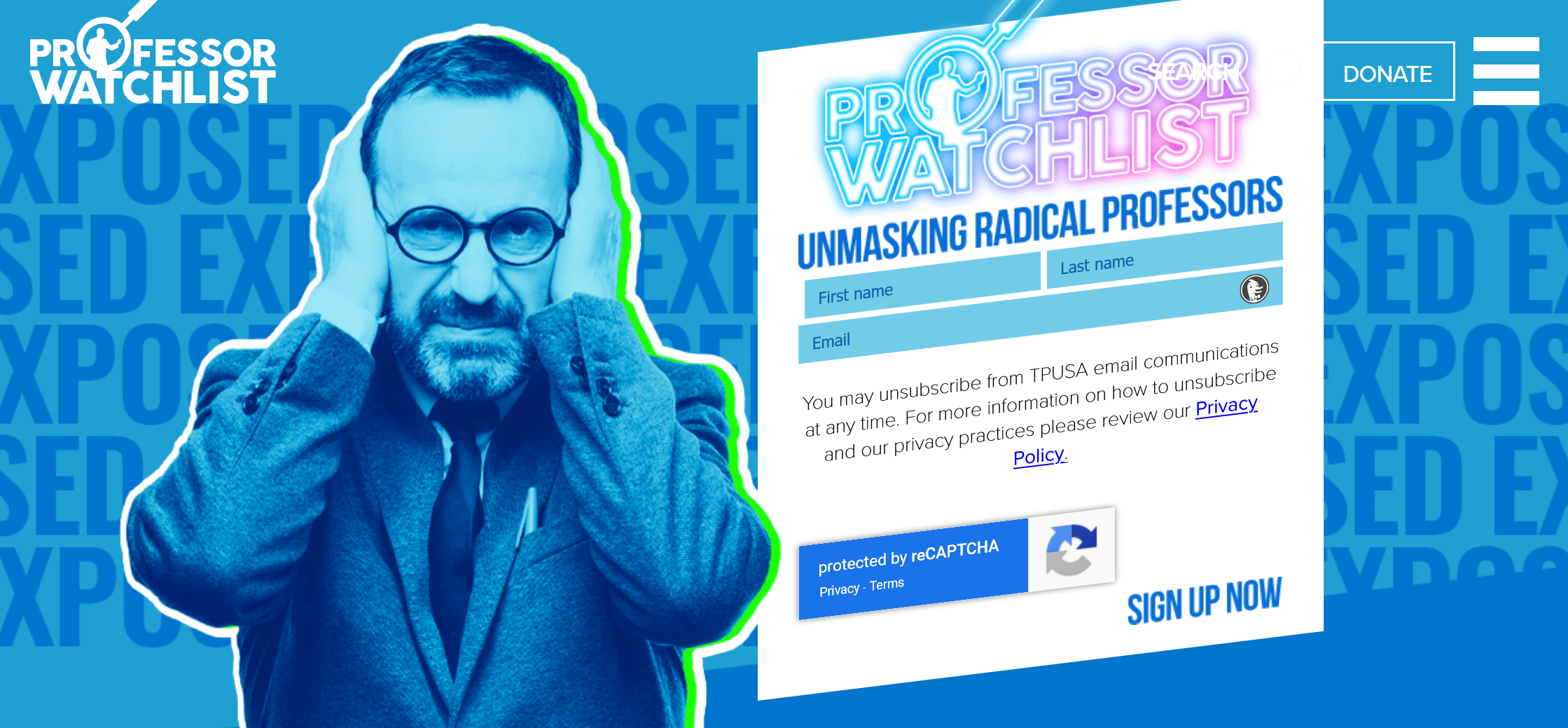

I nevertheless imposed more restrictive limits, and began self-censoring much more, after learning about Kirk’s professor watchlist. This list, which his Turning Point USA organization launched in 2016, promised to “‘expose and document’” faculty who according to this organization “‘discriminate against conservative students, promote anti-American values and advance leftist propaganda in the classroom.’”

I was generally confident that I encouraged students to share whatever perspectives they brought to classrooms, and was reassured by my own criticisms of professional and personal excesses within my union for example or among campus colleagues. At the same time, I was less inclined after students were encouraged to surveil and report their professors to challenge mine to think harder and better, and less convinced that my university would defend me, which I later learned were realistic.

I’ve wanted to believe since before grad school in a model of democratic debate in which interlocutors argued about facts, definitions, values or norms, and relevance, or spaces where such deliberations should be resolved. I’ve assumed that emotions would appear but would with reasoned responses be properly placed within the larger debate.

I never realized how much I had assumed such shared norms among participants, and good faith on their parts, until this era for example of alternative facts and other bad faith efforts. I’m not suggesting that reasonable people cannot debate facts, including their relevance in different debates, but I’m arguing that democratic debate at least as it has been understood in the West for thousands of years doesn’t work without some consensus that such facts exist.

I see no reason why people cannot express sympathy to Kirk’s wife and young children and to others who experience his death as a loss, and even why everyone cannot condemn political violence, and yet do so without ignoring, or worse denying, the damage done by Kirk’s dishonest (and racist and sexist) demagoguery. This damage, which includes his contributions to the return of this destructive administration, was perhaps more widespread than some recognize, and even in the very spaces where some might otherwise admire his efforts.

Leave a Reply