I can understand the appeal of Olga Dies Dreaming by Xochitl Gonzalez as the 2025 One Book One Chicago selection but nonetheless wanted more.

This 2022 novel, which is Gonzalez’s first, tells the semi-autobiographical story of a wedding planner named Olga along with her politician brother Prieto as they confront in their adult lives an absent mother who prefers political activism and a late father who as an addict died from AIDS. It’s the first in what Gonzalez calls a Brooklyn trilogy — the second, which was published in 2024, is Anita De Monte Laughs Last, and the third, which will be released this spring, is Last Night in Brooklyn, and reportedly includes familiar characters, such as Olga’s boyfriend Matteo.

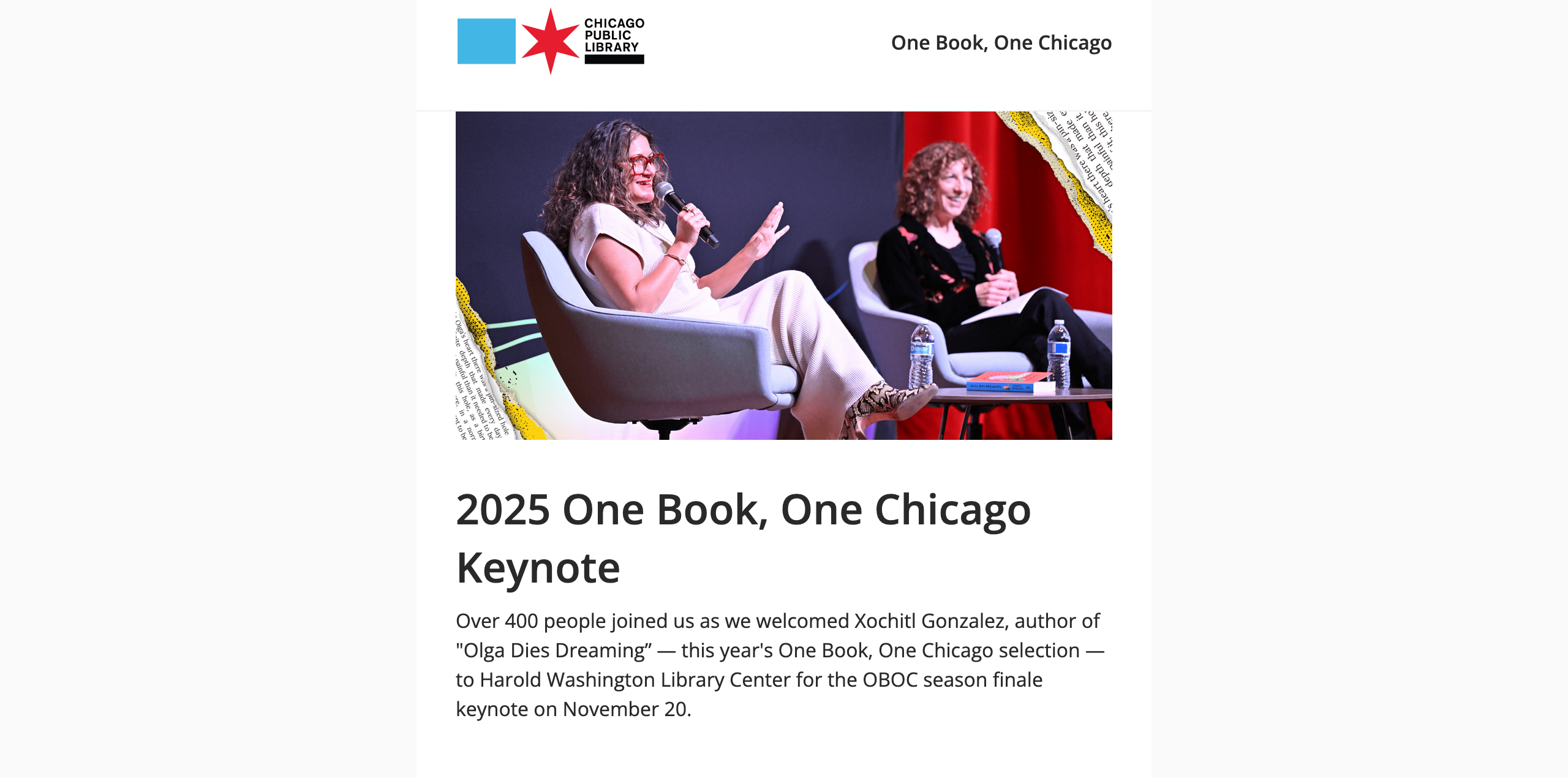

Chicago Public Library Commissioner Chris Brown told the keynote event audience that Gonzalez is the first Puerto Rican author to be selected in the twenty-five years of the One Book One Chicago program, which is obviously appealing. Puerto Ricans, who initially came to Chicago from New York in the 1930s, have been central to the city (e.g., Barrio Borikén) and the country (e.g., the Young Lords).

Gonzalez’s first novel definitely draws upon her ethnic identity, or at least her mother’s contribution — she is also Mexican-American from her father’s side although she was raised by her maternal grandparents. Gonzalez actually wanted to write a book about Puerto Rico and colonialism but decided to make such a book more accessible, and more appealing, as a novel.

Another appeal could be the way it resembles at times a telenovela. Such stories, which might be less prominent in Puerto Rico than for example Mexico, can be widely found, and thus familiar. These telenovela conventions can be recognized in the lost-and-found love or the feuding-mothers-and-daughters themes for example or the fairytale-like ending for both Olga and Prieto.

Both aspects for me are partly why I wanted more. Gonzalez, or her editor, seems unaware of the sections or scenes, such as the letters from Olga’s mother Blanca or a conversation between Olga and her ex-boyfriend Reggie, that seem more like political primers or even mansplaining. Moreover, the conclusion seemed too inconsistent, and too convenient, after conflicts confronted by Olga, Prieto, and others, such as Matteo.

Other readers at least at the One Book One Chicago events I attended had more to say about these characters than the plot. None at one for example seemed to agree that this novel is an older woman’s coming-of-age story, which its publisher suggests is its primary appeal. Such an account would also be consistent with the title, and the allusion to “Puerto Rican Obituary” Olga, who “dies dreaming of a five dollar raise” in a powerful poem by Pedro Pietri.

This Olga doesn’t die, but her evolution is unclear, and ultimately unbelievable. How mature was she if in late in the story she is willing to use her sexuality to exploit her wealthy, and ex-boyfriend, Dick to help Blanca’s political goals, especially when she knows about Matteo’s concerns about trust and abandonment? What happens after the assault that convinces her at the end to bail on her plan to snitch anonymously on her mother’s political activities?

These limitations loom larger in the context of other characters, such as Olga’s Tita Lola who collaborates with Olga’s cousin Mabel to expose Blanca’s perfidy. So where was Tita Lola when Olga was relying upon Blanca’s surrogate, and best friend, Karen? And why wouldn’t Tita Lola have been at least some support for Prieto as he confronted his sexuality, especially when his secrets made him even more vulnerable?

I would be more chagrined if my dissatisfaction were merely the quality of this selection, which would be embarrassingly stereotypical. Rather, I wonder about this selection in regards to the dual One Book One Chicago goals of enlightening Chicagoans and creating community.

One enlightenment possibility could be the way that Olga and Prieto grapple with their diasporic cultural identity. Such syncretic identities based upon my observations can be quite complicated, and certainly relevant to many Chicagoans, and this novel could offer insights that never quite materialize. Neither however seems to understand even at its end what they think being Nuyorican means or even committed to continue coming to terms with it.

Some readers I admit connected with this theme in this book. Several acknowledged in a discussion group I co-moderated for example that this selection made them think about resistance in South Korea from where they had emigrated. That however seemed less from anything in the book and more from the thoughtfulness these readers brought to it.

Community I suppose can come from any shared reading with the right readers even if they agree on the limitations of such a text, which was certainly a minority opinion. At a discussion, my co-moderator gave it the highest rating for example while I offered a more middling one.

I know that choosing a One Book One Chicago selection is challenging. I also believe that my collaboration with those who administer this program has been perhaps the most significant service in my opinion of my academic career, and something I hope to continue even after retiring.

Perhaps that passion produces unrealistic expectations, which could be why this otherwise appealing selection seemed disappointing.

Leave a Reply